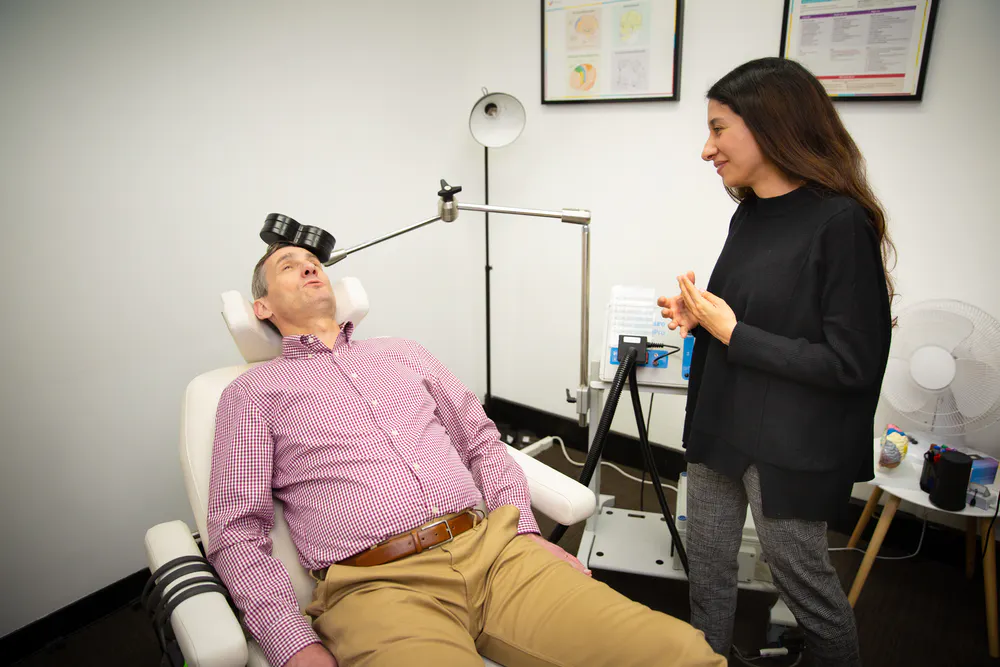

Introduction to TMS Therapy

New data has recently been published providing compelling evidence that clinicians should consider repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) much earlier for patients who do not respond to antidepressant medication. The study focused on 278 individuals with treatment-resistant depression, defined as depression unresponsive to at least two antidepressant medications during their current depressive episode.

Study Design and Treatment Options

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three treatment strategies: 1) switching to the antidepressant venlafaxine XR (or duloxetine if more suitable), 2) adding the atypical antipsychotic medication aripiprazole, or 3) beginning TMS therapy. The Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) was employed to measure outcomes, a standard metric for evaluating the efficacy of antidepressant treatments. Both medication doses and TMS application (delivered via 10Hz pulses to the left frontal cortex) followed standard protocols.

Comparative Results and Efficacy

In primary assessments, TMS significantly outperformed venlafaxine XR in improving MADRS scores. Response rates were notably higher with TMS (52.2%) compared to venlafaxine XR (35.8%) and aripiprazole (38.1%). While these figures were not statistically compared across all three groups simultaneously, the trend favors TMS.

Safety and Tolerability

Regarding safety, TMS exhibited a lower incidence of adverse events (39.3%) compared to venlafaxine XR (49.5%) and aripiprazole (57%). This finding supports earlier studies suggesting that TMS is not only effective but also generally well-tolerated and safer than other treatment options.

Conclusion

The ASCERTAIN-TRD trial and similar studies reinforce the outdated nature of resistance to TMS and provide substantial reassurance to clinicians, patients, service providers, and third-party payers of its safety and efficacy as a treatment option.

Click here if you would like to find out more about being referred to our clinics for TMS

Book an Initial Consultation with Our Experienced Psychiatrists

References: Beck, J. S., & Beck, A. T. (1995). Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. Guilford Press New York; Cosci, F., Guidi, J., Mansueto, G., & Fava, G. A. (2020). Psychotherapy in recurrent depression: efficacy, pitfalls, and recommendations. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 20(11), 1169-1175; George, M. S., Nahas, Z., Molloy, M., Speer, A. M., Oliver, N. C., Li, X.-B., Arana, G. W., Risch, S. C., & Ballenger, J. C. (2000). A controlled trial of daily left prefrontal cortex TMS for treating depression. Biological psychiatry, 48(10), 962-970; Harmer, C. J., Duman, R. S., & Cowen, P. J. (2017). How do antidepressants work? New perspectives for refining future treatment approaches. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(5), 409-418.; Harris, R. (2019). ACT made simple: An easy-to-read primer on acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications.; Kandola, A., Ashdown-Franks, G., Hendrikse, J., Sabiston, C. M., & Stubbs, B. (2019). Physical activity and depression: Towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, 525-539.; Sonmez, A. I., Camsari, D. D., Nandakumar, A. L., Voort, J. L. V., Kung, S., Lewis, C. P., & Croarkin, P. E. (2019). Accelerated TMS for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 273, 770-781.

.png)

About The Author

Dr Ted Cassidy

Dr. Ted Cassidy is a psychiatrist and co-founder of Monarch Mental Health Group in Australia, which provides innovative treatments for depression, PTSD, and anxiety. Monarch Mental Health is recognized as Australia's first outpatient clinic offering assisted therapy and is the largest provider of outpatient magnetic stimulation therapy.